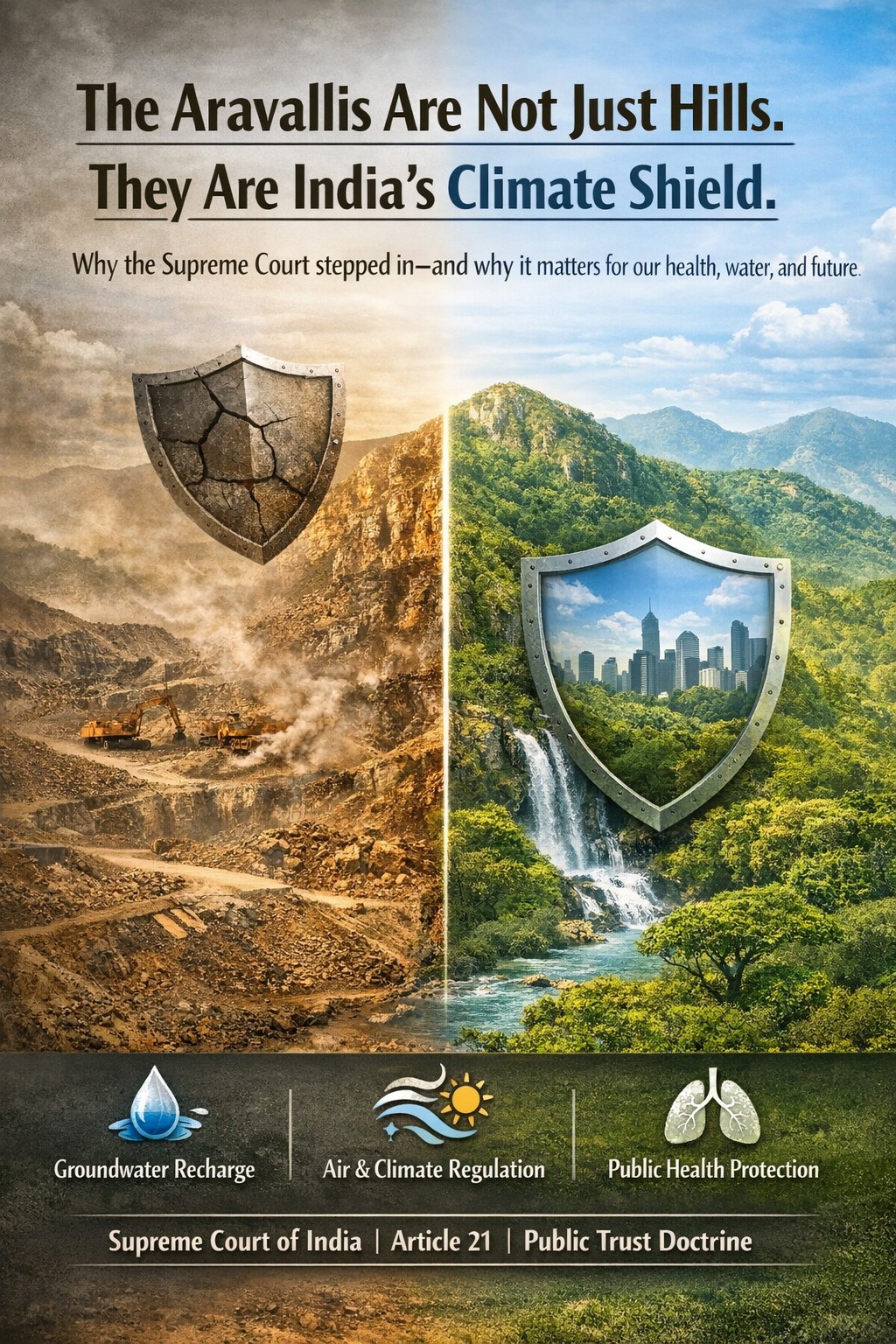

The renewed focus on the Aravalli Hills following the Supreme Court of India’s latest guidelines is not merely an environmental debate—it is a constitutional moment. Stretching across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi, the Aravallis are among the world’s oldest mountain systems and function as a critical ecological shield for north-western India. They prevent desertification from the Thar, recharge groundwater aquifers, regulate regional climate, and support biodiversity that directly sustains human life in one of India’s most densely populated regions.

For decades, their destruction was enabled not by the absence of law but by ambiguity. Large parts of the Aravallis were classified as “revenue land” or “gair mumkin pahad,” allowing mining and construction to proceed despite irreversible ecological damage. The Supreme Court has now decisively addressed this governance failure by mandating a uniform, science-based definition of the Aravalli Hills and Ranges, cutting through administrative loopholes that diluted environmental protection. In doing so, the Court reaffirmed that revenue records cannot negate ecological identity.

The Court’s directions go further: i.e., by ordering a landscape-level Management Plan for Sustainable Mining (MPSM) and restraining the grant of new mining leases until such a plan is in place, the Supreme Court has invoked the precautionary principle in its truest sense. This approach recognises that piecemeal approvals, without cumulative impact assessment, violate the public trust doctrine, under which the State holds natural resources as a trustee for present and future generations.

The implications for human health are profound. Mining-induced dust, silica exposure, groundwater depletion, and habitat fragmentation are not abstract environmental harms—they translate into respiratory diseases, water scarcity, heat stress, and a decline in the quality of life across Delhi-NCR and adjoining regions. In constitutional terms, the destruction of the Aravallis strikes at the heart of Article 21—the right to life, read with Articles 48A and 51A(g), which impose a collective duty to protect the environment.

The Supreme Court’s intervention reframes the Aravallis not as vacant land awaiting development, but as ecological infrastructure essential to climate resilience and public health. The question before governments now is not whether growth should occur, but whether it can happen without dismantling the very systems that make life and development possible. In protecting the Aravallis, the Court has made one thing clear: environmental protection is no longer a discretionary policy—it is enforceable constitutional law.

In the end… “The question is no longer whether the Aravallis can be exploited, but whether the law will be enforced before they are lost beyond repair.”