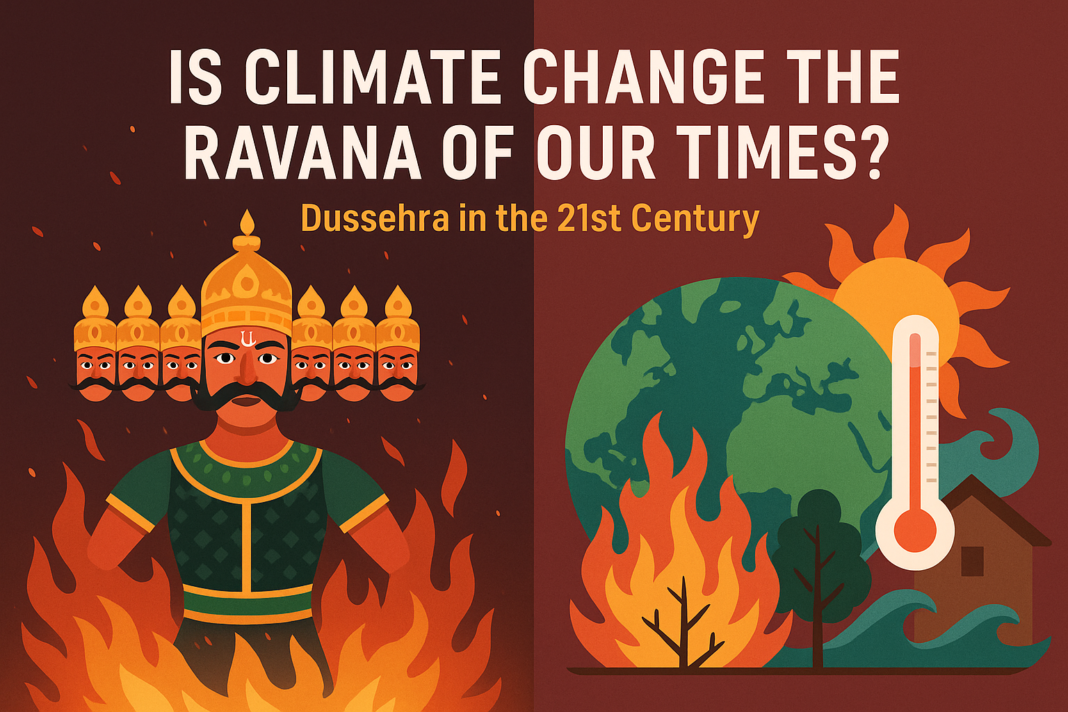

Every autumn, India lights up with the vibrant celebrations of Dusshera—also known as Vijayadashami, a festival that symbolises the eternal triumph of good over evil. The effigies of Ravana, Meghnath, and Kumbhkaran, towering above crowds, go up in flames as people cheer, marking the victory of Lord Rama. Yet, as the smoke rises and the skies darken with fumes, a question lingers:

“In the 21st century, could the festival itself be mirroring one of humanity’s greatest modern battles—our struggle against climate change?“

Climate change, like Ravana, has many heads. From rising global temperatures to extreme weather, from biodiversity loss to plastic pollution, it embodies the very chaos and imbalance that Dusshera warns us against. According to the Indian Meteorological Department and the IPCC, India has already witnessed a 0.7°C rise in average temperature between 1901 and 2018, with projections of an alarming 2.4–4.4°C increase by 2100. What was once the crisp autumn air of October is now increasingly unpredictable—sometimes unseasonal rains drench Ramlila grounds, sometimes heatwaves linger long past the monsoon. Festivals that once followed seasonal cycles now clash with disrupted climate rhythms.

Then comes the fire—the centrepiece of Dusshera. Burning Ravana’s effigy has always symbolised the destruction of arrogance and evil. But ironically, this act today adds to the very evil we are fighting. A single 50-foot effigy can emit 50–60 kilograms of CO₂ equivalent gases, while synthetic paints, plastics, and fabrics release toxic chemicals and heavy metals into the air. In Delhi, where October is already marred by stubble burning, effigy fires, and fireworks, these activities push PM2.5 levels up by 30–40%. What was once a ritual of purification has now become an act that pollutes. As we cheer Ravana’s fall, we may unknowingly be feeding a larger, more menacing Ravana—air pollution and climate change itself.

In fact, it becomes even more ironic when we recall the epic itself. In the Ramayana, Lanka was set ablaze. Today, our own lands burn—not as myth but as reality. The Amazon wildfires, Australian bushfires, and Uttarakhand’s forest infernos have consumed millions of hectares of green cover. Between 2001 and 2022 alone, India lost 2.3 million hectares of tree cover (Global Forest Watch). Like Lanka, our Earth is also being scorched, only this time not by divine arrows, but by human choices. The flames of Ravana’s effigy on a festive night echo eerily with the flames that engulf our forests in the age of climate change.

Even the fireworks that light up Dusshera skies add their burden. Beyond their sparkle, they release sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter that aggravate asthma, lung disease, and heart conditions. According to The Lancet, air pollution already causes approximately 1.6 million premature deaths in India each year. Meanwhile, the festival’s growing reliance on energy-intensive light shows, sound systems, and mass gatherings amplifies its carbon footprint. Dusshera, in many ways, has shifted from being a purely symbolic act of cleansing to an event that ironically adds to the chaos of our environment.

Yet, just as every myth holds hope, so too does this reality. Across India, communities are experimenting with new ways to celebrate. In Delhi and West Bengal, artisans now build effigies from bamboo, straw, and clay, painted with natural colours instead of synthetic toxins. Some cities have replaced fireworks with dazzling laser light shows—turning Ravana’s fall into a spectacle that dazzles without choking the air. Elsewhere, symbolic burnings are practised—more miniature eco-friendly effigies are burnt while larger replicas remain unburnt, preserving the tradition without harming the skies. These innovations suggest that Dusshera can evolve, keeping its symbolism intact while embracing environmental responsibility.

The mythology itself offers lessons for our modern crisis. Rama did not defeat Ravana solely through sheer might; instead, it was strategy, alliances, and collective effort that led to victory. In today’s world, defeating the “Ravana” of climate change also requires alliances—not of armies but of governments, scientists, corporations, and ordinary people. Just as Rama had the Vanarasena (monkey army), we need a “climate sena” that unites across boundaries. Just as Ravana’s arrogance led to his fall, our arrogance in overconsumption and disregard for nature could become our downfall. If climate change has ten heads, then perhaps science, policy, and human conscience together form Rama’s bow and arrow.

The parallel becomes even more profound when we view Dusshera’s message in a global context. Celebrated not only in India but across Nepal, Bangladesh, and parts of Southeast Asia, its essence—that evil can be defeated—resonates across cultures. Similarly, climate change knows no borders. Forests burning in the Amazon alter rainfall patterns in India, melting glaciers in the Himalayas threaten coastal regions in Europe, and pollution in Asia impacts global air circulation. The very universality of Dusshera’s message mirrors the universality of the climate crisis—it is not a local fight, but a collective human struggle.

And so, perhaps the real correlation between Dusshera and climate change lies in symbolism. Ravana was not invincible; he fell when people united under a common cause. Climate change, too, though daunting, is not unconquerable. If a tree-planting initiative could follow every effigy burning, if every firecracker could be replaced with a light show, and if every family pledged a sustainable act, then Dussehra would not just mark the destruction of evil—it would mark the birth of a new ecological consciousness.

This Dusshera, as Ravana’s effigies turn to ash, we must ask ourselves:

“Are we burning away arrogance and greed, or are we adding fuel to them?”

The festival reminds us that no evil is too great to be defeated. If Ravana could be brought down, so too can climate change—provided we see it for what it is: the Ravana of our times.

Till we meet again…